On Translating Amalie Smith’s THREAD RIPPER: A Conversation with Jennifer Russell

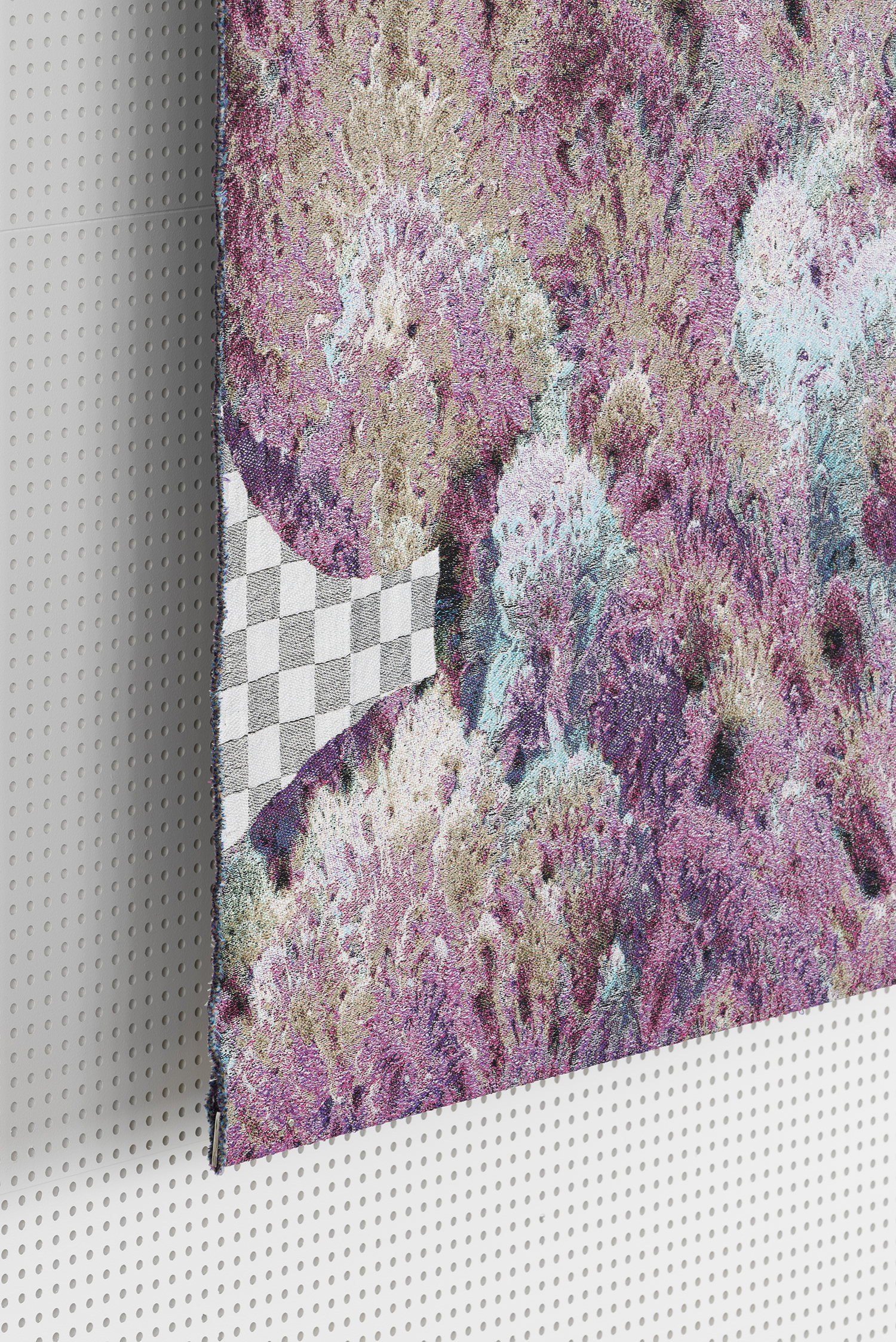

Close-up of Amalie Smith’s Machine Learning, photo by David Stjernholm

Rosie Ellison-Balaam spoke to Jennifer Russell about her translation of Amalie Smith's Thread Ripper, to mark its publication today. Russell discusses her attraction to the project and approach to its translation, from navigating Smith's textured, multi-strand novel, being introduced to the pioneering mathematician Ada Lovelace, and the challenges of writing like a machine. Russell carefully handles Smith's writing – her short evocative lines, poetic and measured, are translated word by word, and her research into looms, Lovelace's letters, and AI text generators are intimately retraced.

What drew you to translating Thread Ripper?

A few years before Thread Ripper was published, I translated some text to accompany the exhibition of three tapestries Amalie Smith created as a public commission for Ørestad Gymnasium, a high school in Copenhagen, which are permanently on display there (so you can go see them if you’re in the neighbourhood!). These tapestries are the same ones that feature in Thread Ripper, and it’s a good example of Smith’s interdisciplinary practice: her investigations unfold across several different mediums, morphing and connecting and taking shape as hybrid works. I was intrigued to see how the ideas behind the tapestries would materialise in book form.

And then, when reading the book, I was fascinated by its unique structure and the way it shapes the reading experience. The different strands play out on opposite sides of the book, so as a reader you alternate between them, going back and forth from one side of the book to the other in whatever way you please, quite literally weaving them together as you read (and appropriately, text, from texere, to weave). As is characteristic of Smith’s work, form and content are inextricable. I was surprised by how naturally the story came together as you wove back and forth, intuitively creating your own path through the book. And, as always, I was attracted to Smith’s deceptively simple, poetic prose that wavers between and brings together the very abstract and the very concrete.

Amalie Smith’s Machine Learning, photo by David Stjernholm

And you had of course previously translated Amalie Smith’s novel Marble, published by Lolli in 2020. Did you find the process was different second time around?

The process was similar in many ways, because both books are based on a lot of research – historical, biographical, technological. Translating Smith’s works has required that I retrace her steps through the research material: with Marble, I read about infrared photography, sponge-diving, and explored Google street views of the Acropolis; when translating Thread Ripper, I made my way through Ada Lovelace’s letters, learned about looms and GPT-3 technology, and played with AI text generators.

Then there is a poetic quality to Smith’s writing; the books are not particularly long and her sentences are often quite brief, clipped even, and at the same time, very vivid and evocative. This is even clearer in Thread Ripper, where so many sentences stand on single lines, reverberating in all the blank space around them. Translating it feels like translating poetry; I am working very much word by word, attentive to how it sounds, how it works in the sentence.

Smith’s novel weaves fiction with the life of an influential female figure, had you encountered Ada Lovelace before working on the book, and has your relationship to her through the process of translation changed?

Shamefully, or perhaps – sadly – unsurprisingly, as is so often the case with pioneering women in history, I hadn’t heard of Ada Lovelace until I encountered her in Smith’s work. Getting to know a historical figure through their own words, by reading their letters, as I did with Lovelace when doing research for the translation, feels very intimate. Translation is always an intimate act – you are adopting the voice of the writer, making yourself into a channel – but this felt even more pronounced when translating the sections written by Ada’s Algorithm. Just as the algorithm is fed Lovelace’s letters in order to generate text, I too tried to absorb her writing so my translation would echo her voice.

These machine-generated sections are also peppered with odd statements which are in fact obscure references to actual biographical details from Lovelace’s life. In translating, these felt like little clues, and I would go look them up to find out the back story: how as a 12-year-old, Lovelace drew plans for a steam-powered flying machine in the shape of a horse, how she called her notes to Charles Babbage’s lecture her ‘first-born’, how she began gambling on horses (perhaps, it is said, to test out a mathematical scheme she had invented to predict the winner) and lost so much money she had to pawn her jewellery to pay back the debt, or how Charles Dickens read aloud from one of his novels at her deathbed.

Amalie Smith’s Machine Learning, photo by David Stjernholm

The novel is made of these narrative strands, from Lovelace, Penelope and Odysseus, and the contemporary weaver, each distinguished in print by their layout on the page, or font. How did you tackle such a complex text? Did you work on it as it appears through the book, or work on each story individually?

I ended up working on each part individually, although purely out of technical necessity. I would have liked to work on the text as it appears in the book, and I know that’s how Amalie originally wrote it, but without the right computer program it got too messy. Perhaps this was for the best, because it helped me keep the tone and voice of each strand distinct. And hopefully, the connections and resonances between the strands, across the pages, come through even though I wasn’t focused on that specifically when translating.

Were there any particular challenges during the translation? And how involved was Amalie?

Capturing the different narrative voices was tricky, but the machine-generated voice of Ada Lovelace was particularly challenging. Because the (fictional) algorithm is fed Ada Lovelace’s (actual) letters, the text it generates reads as simultaneously archaic and machine-like. It has an uncanny quality to it, hovering somewhere between the real and fictional – the narrator says she can’t help but feel as though Ada Lovelace exists as a spectre, speaking to her from inside the machine. I felt the same way as a reader; I couldn’t quite tell how far the fiction stretched – was the text really machine-generated, or did Amalie Smith write it? (She did.)

In the original (Danish) work, the text generated on the basis of Ada’s letters is machine-translated into Danish. The machine nature of this voice is therefore quite obvious: it’s riddled with English phrasings and English idioms translated very literally into Danish. I couldn’t replicate this in the English translation, of course: in the fiction, no machine translation is necessary, because Ada’s letters are already written in English. Instead, I had to find other ways of making Ada’s AI-voice noticeably machine-like. I played with text generators to get an idea of what ‘machine-writing’ sounds like. Often it’s eerily difficult to tell, but I found the giveaway was often a jarring use of vocabulary, non-sequiturs, a missing sense of logic. I don’t know how well I succeeded, but hopefully these sections come across as slightly ‘off’ in a way that gives pause.

What are you working on now?

I am working on a co-translation of another Lolli book, My Work, by Olga Ravn, with my fellow translator, Sophia Hersi Smith, to be published by Lolli in 2023!

JENNIFER RUSSELL has published translations of Amalie Smith, Christel Wiinblad, and Peter-Clement Woetmann. She was the recipient of the 2019 Gulf Coast Prize for her translation of Ursula Scavenius’s ‘Birdland’, and in 2020 she received an American-Scandinavian Foundation Award for her co-translation of Rakel Haslund-Gjerrild's All the Birds in the Sky. In 2021, she was shortlisted for the TA First Translation Prize, for her translation of Amalie Smith’s Marble.

AMALIE SMITH (b. 1985) is a Danish writer and visual artist. A graduate from the Danish Academy of Creative Writing and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Smith has received numerous awards for her work, including the Danish Arts Foundation’s prestigious three year working grant. Thread Ripper is her second novel published in English translation. Marble was published by Lolli in 2020.

Thread Ripper by Amalie Smith translated by Jennifer Russell, publishes today. Purchase your copy here.